Preface: The Caspian Sea Summit and the Historical Crossroads of the 21st Century

This article is

part of The Sino-Russia Alliance: Challenging America’s

Ambitions in Eurasia (September 23, 2007). For

editorial reasons the article is being published by Global Research in

three parts. It is strongly advised that readers also study the prior

piece.

History is in the making. The Second Summit of Caspian Sea

States in Tehran will change the global geo-political environment. This article

also gives a strong contextual background to what will be in the backdrop at

Tehran. The strategic course of Eurasia and global energy reserves hangs in

the balance.

It is no mere chance that before the upcoming summit in Tehran that three important post-Soviet organizations (the Commonwealth of Independents States, the Collective Security Treaty Organization, and the Eurasian Economic Community) simultaneously held meetings in Tajikistan. Nor is it mere coincidence that the SCO and CSTO have signed cooperation agreements during these meetings in Tajikistan, which has effectively made China a semi-formal member of the CSTO alliance. It should be noted that all SCO members are also members of CSTO, aside from China.

This is all in addition to

the fact that the U.S. Secretary of State, Condoleezza Rice, and the U.S.

Secretary of Defence, Robert Gates, were both in Moscow for important, but

mostly hushed, discussions with the Kremlin before Vladimir Putin is due to

arrive in Iran. This could have been America’s last attempt at breaking the

Chinese-Russian- Iranian coalition in Eurasia. World leaders will watch for

any public outcomes from the Russian President’s visit to Tehran. It is

also worth noting that NATO’s Secretary-General was in the Caucasus region for a

brief visit in regards to NATO expansion. The Russian President will also be in

Germany for a summit with Angela Merkel before arriving in

Tehran.

On five fronts there is antagonism

between the U.S. and its allies with Russia, China, and their allies: East

Africa, the Korean Peninsula, Indo-China, the Middle East, and the Balkans.

While the Korean front seems to have calmed down, the Indo-China front has been

heated up with the start of instability in Myanmar (Burma). This is part of the

broader effort to encircle the titans of the Eurasian landmass, Russia and

China. Simultaneous to all this, NATO is preparing itself for a possible

showdown with Serbia and Russia over Kosovo. These preparations include

NATO military exercises in Croatia and the Adriatic Sea.

In May, 2007 the Secretary-General of CSTO, Nikolai Bordyuzha invited Iran to apply to the Eurasian military pact; “If Iran applies in accordance with our charter, [CSTO] will consider the application,” he told reporters. In the following weeks, the CSTO alliance has also announced with greater emphasis, like NATO, that it too is prepared to get involved in Afghanistan and global “peacekeeping” operations. This is a challenge to NATO’s global objectives and in fact an announcement that NATO no longer has a monopoly as the foremost global military organization.

The globe is becoming further militarized than what it already is by two military blocs. In addition, Moscow has also stated that it will now charge domestic prices for Russian weaponry and military hardware to all CSTO members. Also, reports about the strengthening prospects of a large-scale Turkish invasion of Northern Iraq are getting stronger, which is deeply related to Anglo-American plans for balkanizing Iraq and sculpting a “New Middle East.” A global showdown is in the works.

Finally, the Second Summit

of Caspian Sea States will also finalize the legal status of the Caspian

Sea. Energy resources, ecology, energy cooperation, security, and

defensive ties will also be discussed. The outcome of this summit will

decide the nature of Russo-Iranian relations and the fate of Eurasia. What

happens in Tehran may decide the course of the the rest of

this century. Humanity is at an important historical crossroad. This is why

I felt that it was important to release this second portion of the original

article before the Second Summit of the Caspian Sea

States.

Mahdi Darius Nazemroaya, Ottawa, October 13,

2007.

The haunting spectre of

a major war hangs over the Middle East, but war is not

written in stone. A Eurasian-based counter-alliance, built around the

nucleus of a Chinese-Russian- Iranian coalition also makes an Anglo-American

war against Iran an unpalatable option that could turn the globe

inside-out. [1]

America’s superpower status would in all likelihood

come to an end in a war against Iran. Aside from these factors, contrary to the

rhetoric from all the powers involved in the conflicts of the Middle East

there exists a level of international cooperation between all parties. Has the

nature of the march to war changed?

Tehran’s Rising Star:

Failure of the Anglo-American attempt to Encircle and Isolate

Iran

Shrouded

in mystery are the dealings between Iran and the Republic of Azerbaijan during

an August, 2007 meeting between President Ahamdinejad and President

Aliyev. Both leaders signed a joint declaration in Baku on August 21, 2007

stating that both republics are against foreign interference in the affairs

of other nations and the use of force for solving problems. This is a direct

slur at the United States. Baku also reemphasized its recognition of Iran’s

nuclear energy program as a legitimate right.

However, the meetings

between the two sides took place after a few months of meetings

between Baku and the U.S. together with NATO officials.

Baku seems

to be caught in the middle of a balancing act between Russia, Iran, America, and

NATO. At the same time as the meetings between the Iranian President and Aliyev

in Baku, Iranian officials were also in Yerevan holding talks

with Armenian officials.

This could be part of an Iranian

attempt to end tensions between Baku and Yerevan, which would benefit Iran

and the Caucasus region. The tensions between Yerevan and Baku have been

supported by the U.S. since the onset of the post-Cold War era, with

Baku within the U.S. and NATO spheres of influence.

At first glance, Iran has been busy engaging in what can be called a counter-offensive to American encroachment. Iranian officials have been meeting with Central Asian, Caucasian, Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), and North African leaders in a stream of talks on security and energy. The SCO meeting in Kyrgyzstan was one of these. The importance of the gathering was highlighted by the joint participation of the Iranian President and the Secretary-General of the Supreme Security Council of Iran, Ali Larijani.

Iran’s

dialogue with the presidents of Turkmenistan, the Republic of

Azerbaijan, and Algeria are part of an effort to map out a unified energy

strategy spearheaded by Moscow and Tehran. Iran and the Sultanate of Oman

are also making arrangements to engage in four joint oil projects in the Persian

Gulf. [2]

Iran has also announced that it will start construction

of an important pipeline route from the Caspian Sea to the Gulf of Oman.[3]

This project is directly linked to Iranian talks with Turkmenistan and the

Republic of Azerbaijan, two countries that share the Caspian Sea with

Iran. Furthermore, after closed-door discussions with Iranian officials,

the Republic of Azerbaijan has stated that it is interested in

cooperating with the SCO. [4] In addition, Venezuela, Iran, and Syria are

also coordinating energy and industrial projects.

The Nabucco Project, Eurasian Energy Corridors, and the

Russo-Iranian Energy Front

Across Eurasia strategic energy corridors are being developed. What do these international developments insinuate? A Eurasian-based energy strategy is taking shape. In Central Asia, Russia, Iran and China have essentially secured their own energy routes for both gas and oil. This is one of the reasons all three powers in a united stance warned the U.S. at the SCO’s Bishkek Summit, in Kyrgyzstan, to stay out of Central Asia. [5]

In part

one of the answers to these questions leads to the Nabucco Project, which will

transport natural gas from the Caucasus, Iran, Central Asia, and the Eastern

Mediterranean towards Western Europe through Turkey and the Balkans. Spin-offs

of the energy project could include routes going through the former

Yugoslav republics. Egyptian gas is even projected to be connected to the

pipeline network vis-à-vis Syria. There is even a possibility that Libyan gas

from Libyan fields near the Egyptian border may be directed to European

markets through a route going through Egypt, Jordan, and Syria which will

connect to the Nabucco Pipeline.

At first glance, it appears that

the transport of Central Asian gas, under the Nabucco Project, through a

route going through Iran to Turkey and the Balkans is detrimental to Russian

interests under the terms of the Port Turkmenbashi Agreement signed by

Turkmenistan, Russia, and Kazakhstan. However, Iran and Russia are allies and

partners, at least in regards to the energy rivalry in Central Asia and the

Caspian Sea against the U.S. and the European Union.

In May,

2007 the leaders of Turkmenistan, Russia, and Kazakhstan also

planned the inclusion of an Iranian energy route, from the Caspian Sea to

the Persian Gulf, as an extension of the Turkmenbashi

Agreement. A route going through either Russia or Iran is

mutually beneficial to both countries. Both Tehran and Moscow have

been working together to regulate the price of natural gas on a global

scale. If Turkmen gas goes through Russian or Iranian territory, Moscow

will profit either way. Both Tehran and Moscow have hedged their bets in a

win-win situation.

Russia is also involved in the Nabucco Project

and has secured a Balkan energy route for the transportation of fuel to

Western Europe from Russia vis-à-vis Greece and Bulgaria. To this end

on May 21, 2007 the Russian President arrived in Austria to discuss energy

cooperation and the Nabucco Project with the Austrian government. [6] One of the

outcomes of the Russian President’s visits to Austria was the opening of a large

natural gas storage compound, near Salzburg, with a holding capacity of 2.4

billion cubic metres. [7] The Nabucco Project and a united Russo-Iranian energy

initiative are also the main reasons that the Russian President will visit

Tehran for an important summit of leaders from the Caspian Sea, in

mid-October of 2007.

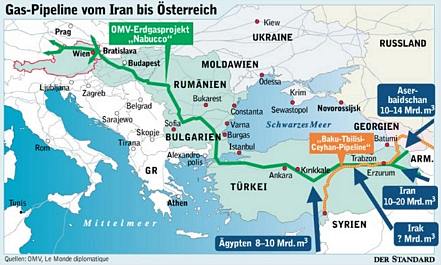

Map: Contours of the

Nabucco Project

© Jan Horst Keppler, European Parliament (Committee on

Foreign Affairs), 2007.

One might

ask if Russia, Iran, and Syria are surrendering to the demands of America

and the E.U. by providing them with what they sought in the first place.

The answer is no. The Franco-German entente is very interested in the

Nabucco Project and through Austria has much at stake in the energy project.

French and German energy firms also want to get involved as are Russian and

Iranian companies. This is also one of the reasons Vienna has been vocally

supporting Syria and Iran in the international arena. Total S.A., the giant

French-based energy firm, is also working with Iran in the energy

sectors.

Tehran,

Moscow, and Damascus have not been fully co-opted; they are acting in their

national and security interests. However, the national interests of modern

nation-states should also be scutinized further. The leverage Moscow and

Tehran now have can be used to drive a wedge between the Franco-German

entente and the Anglo-American alliance. A case in standing is the initial

willingness of France and Germany to accept the Iranian nuclear energy program.

It is believed in Moscow and Tehran that the Franco-German entente could be

persuaded to distance itself from the Anglo-American war agenda with the right

leverage and incentives.

This could also be one of the factors for

the marine route of the Nord Stream gas pipeline, which runs from Russia

through the Baltic Sea to Germany and bypasses existing energy

transit routes going through the Baltic States, Ukraine, Belarus,

Slovakia, the Czech Republic, and Poland. Eastern Europe is part of what is

called “New Europe” as a result of Donald Rumsfeld’s 2003 comments that

only “Old Europe,” meaning the Franco-German entente, was against

the Anglo-American invasion of Iraq. [8] For example Poland is an

Anglo-American ally and could block the transit of gas from Russia to Germany if

it was prompted to do so by Britain and America. Moreover, Russia could exert

pressure on these Eastern European countries by cutting their gas supplies

without effecting Western Europe. Several of these Eastern European states also

were pursuing transit fee schemes and reduced gas prices because of their

strategic placements as energy transit routes.

Russia

and Iran are also the nations with the largest natural gas reserves in the

world. This is in addition to the following facts; Iran also exerts influence

over the Straits of Hormuz; both Russia and Iran control the export of Central

Asian energy to global markets; and Syria is the lynchpin for an Eastern

Mediterranean energy corridor. Iran, Russia, and Syria will now exercise a great

deal of control and influence over these energy corridors and by extension the

nations that are dependent on them in the European continent. This is another

reason why Russia has built military facilities on the Mediterranean shores

of Syria. The Iran-Pakistan- India gas pipeline will also further strengthen

this position globally.

Map:

Nabucco Gas Pipeline Project Gas Supply Sources for Nabucco

© Nabucco Gas

Pipeline International GmbH, 2007.

Map: Levantine

Energy Corridor

© Mahdi Darius Nazemroaya, Global Research,

2007.

Map:

Gas-Pipeline vom Iran bis Österreich

English translation from German:

Gas Pipeline from Iran to Austria

© Der

Standard, 2007.

The Baltic-Caspian- Persian Gulf Energy

Corridor: The Mother of all Energy Corridors?

To add to all

this, American and British allies by their very despotic and self-concerned

natures will not hesitate to realign themselves, if presented with the

opportunity, with Russia, China, and Iran. These puppet regimes and

so-called allies, from Saudi Arabia and Kuwait to Egypt, have no personal

loyalties and are fair-weather allies. If they can help it, the moment they

believe that they can no longer benefit from their

relationships as clients they will try to abandon the Anglo-American camp

without hesitation. Any hesitation on their part will be in regards to their own

political longevity. Iran, Russia, and China have already been in the

long process of courting the leaders of the Arab Sheikhdoms of the Persian

Gulf.

The ultimate aim of Russo-Iranian energy cooperation will be the

establishment of a north-south energy corridor from the Baltic Sea to

the Persian Gulf and with the Caspian Sea as its mid-axis. An east-west

corridor from the Caspian Sea, Iran, and Central Asia to India and China will

also be linked to this. Iranian oil could also be transported to

Europe through Russian territory, hence bypassing the sea and consolidating

Russo-Iranian control over international energy security. If other states in the

Persian Gulf were included into the equation a dramatic seismic shift in the

global balance of power could occur. This is also one of the reasons that the

oil-rich Arab Sheikhdoms are being courted by Russia, Iran, and

China.

Eurasian Energy Corridors:

Two-Edged Knives?

However,

the creation of these energy corridors and networks is like a two-edged sword.

These geo-strategic fulcrums or energy pivots can also switch their

directions of leverage. The integration of infrastructure also leads towards

economic integration. If other factors in the geo-political equations are

changed or manipulated, the U.S., Britain, and their partners might wield

control over these routes. This is one reason why Zbigniew Brzezinski stated

that the creation of a Turkish-Iranian pipeline would benefit America. [9] It

should also be noted that Turkey will also be jointly developing three

gas projects in the South Pars gas fields with Iran.

[10]

If regime change were initiated in Iran or Russia or one of the

Central Asian republics the energy network being consolidated and strengthened

between Russia, Central Asia, and Iran could be obstructed and ruined.

This is why the U.S. and Britain have been desperately promoting covert and

overt velvet revolutions in the Caucasus, Iran, Russia, Belarus,

Ukraine, and Central Asia. To the U.S. and E.U. the creation of a

Baltic-Caspian- Persian Gulf energy grid is almost the equivalent, in regards to

energy security, of a “Unipolar World,” but only not in their

favour.

The “Great Game” Enters the Mediterranean Sea

The title “Great Game” is a term that originates from the struggle between Britain and Czarist Russia to control significant portions of Eurasia. The term is attributed to Arthur Conolly. A romanticized British novel, Kim, written by Rudyard Kipling and published in 1901 arguably immortalized the concept and term. This Victorian novel was a suspenseful story about the competition between Czarist Russia and Britain to control the vast geographic stretch that included Central Asia, India, and Tibet. In reality the “Great Game” was a struggle for control of a vast geographic area that not only included Tibet, the Indian sub-continent, and Central Asia, but also included the Caucasus and Iran. Additionally, it was London that was the primary antagonist, because of British attempts to enter Russian Central Asia. In fact the British had spying networks and facilities in Khorason, Iran and in Afghanistan that would operate against the interests of St. Petersburg in Russian Central Asia.

A

contemporary version of the “Great Game” is being played once again for control

of roughly the same geographic stretch, but with more players and greater

intensity. Central Asia became the focus of international rivalry after the

collapse of the former U.S.S.R. and the end of the Cold War. For the most part

Central Asia, aside from Afghanistan, has been insulated. It has

been the Middle East and the Balkans where this contest has been

playing itself out violently.

The “Great Game” has also taken new

dimensions and has entered the Mediterranean. This gradual outward movement

has been creeping in a westward direction from the Middle East and the

Balkans as the area of contention is expanded. This is not a

one-directional competition. With the drawing in of Algeria, this push has

reached the Western Mediterranean or the “Latin Sea” as Halford J. Mackinder

refers to it, whereas before it was limited to the Eastern Mediterranean. This

extension of the area of the “Great Game” is also a result of the outward push

from Eurasia of the Eurasian-based alliance of Russia, Iran, and China. Examples

of this are the emerging inroads China is making in the African continent and

Iran’s alliances in Latin America.

However, in reality the Mediterranean

region is no stranger to international rivalry or conflicts similar to the

“Great Game.” The Second Turkish-Egyptian War (1839-1849), also called the

Syrian War, was a historical example of this. It was during this war that Beirut

was bombarded by British warships. The Ottoman Empire, supported by Britain,

Czarist Russia, and the Austrian Empire, was facing-off against an expansionist

Egypt, which was supported by Spain and France. The whole conflict had the

overtones of underlying rivalries between Europe’s major powers. Another

example is the three Punic Wars between the ancient Carthagians and

the Romans.

Gas, Oil, and Geo-Politics in the Mediterranean

Sea

The Mediterranean has literally become an extension to the

international and dangerous rivalries for control of Central Asian and Caucasian

energy resources. Libya, Syria, Lebanon, Algeria, and Egypt are all Arab

countries involved. Algeria already supplies gas to the E.U. through the

Trans-Mediterranean Pipeline which runs to the Italian island of

Sicily via Tunisia and the Mediterranean Sea. Niger and Nigeria are

also building a natural gas pipeline that will reach the E.U. via

Algerian energy infrastructure. Libya also supplies gas to the E.U

through the Greenstream Pipeline which connects to Sicily via an underwater

route in the Mediterranean Sea.

Russia and Iran are spearheading a

move to bring Algeria into their orbit in order to establish a gas cartel. If

Algeria, and possibly Libya, can be brought into the orbits of Moscow and Tehran

the leverage and influence of both would be greatly increased and both would

tighten their control over global energy corridors and European energy

supplies. Approximately 97 percent of the projected amount of natural

gas that will be imported by continental Europe would be controlled by

Russia, Iran, and Syria under such an arrangement, whereas without Algeria

approximately 93.6 percent of the natural gas exported would be controlled.

[11] Algeria is also the sixth largest exporter of oil to the U.S., following

behind Canada, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, Venezuela, and Nigeria.

Western and

Central European energy security would be under tight controls from Russia,

Iran, Turkey, Algeria, and Syria because of their control over the geo-strategic

energy routes. This is one of the reasons that the E.U. has unsuccessfully tried

to force Russia to sign an E.U. energy charter that would obligate Moscow to

supply energy to the E.U. and one of the reasons that NATO is considering

using Article 5 of its military charter for energy security. [12] In

addition, the Security and Prosperity Partnership of North America obligates

America’s top energy sources, Canada and Mexico, to supply the U.S.

with oil and gas. Worldwide the securing of energy resources has become an issue

of force and involuntary compulsion.

Map:

Missing link between giant sources (in bcm) and potential markets

Note: The

missing link implied is the Nabucco Pipeline, giant sources are the Middle East

and former Soviet Union, and potential markets are the western and

central members of the European Union.

© Nabucco Gas Pipeline

International GmbH, 2007.

Oceania versus Eurasia in the Mediterranean

Littoral

“...we might weld together the West and the East, and permanently penetrate the Heartland with oceanic freedom.”

-Sir Halford J. Mackinder (Democratic Ideals and Reality, 1919); In regards to “oceanic freedom” refer to George Orwell’s definition or warning in Nineteen Eighty-Four.

It was also in the Mediterranean Sea that the geo-strategic paradigm

of sea-power versus land-power that was observed by Halford Mackinder first

came into play. [13] Mackinder put forward the concept, which one

is tempted to almost label as organic, that rival powers or entities,

as they expand, would compete for dominance in a certain area and as they

reached maritime areas this competition would eventually be taken to the seas as

both powers would try and turn the maritime area into a lake under their own

total control. This is what the Romans did to the Mediterranean

Sea. It was only once a victor emerged from these

competitions that the emphasis on naval power would decline in the maritime

areas.

According to Mackinder, the First World War was “a war between

Islanders [e.g., Britain, the U.S., Australia, New Zealand, and Japan] and

Continentals [Eurasians; e.g., Germany, Austro-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire],

there can be no doubt about that.” [14] Also, according to Mackinder

it was dominant sea-power that won the First World War.

Naval

power has clearly had a cutting edge over land-power in establishing empires.

Western European nations like Britain, Portugal, and Spain are all

examples of nations that became thalassocracies, empires at

sea. Through the control of the seas an island-nation with no land borders

with a rival can invade and eventually expand into a rival’s territory.

The Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI) is a modern embodiment

of Halford J. Makinder’s oceanic-power versus land-power paradigm. [15] The

Anglo-American alliance and their allies represent oceanic-power,

while the Eurasian-based counter-alliance, based around the nucleus of

a Chinese-Russian- Iranian coalition, represents

land-power.

It can also be observed that historically Eurasian

economies did not require far-reaching trade and could exist within a

smaller geographic trading area, while the economies of the oceanic powers such

as Britain and the U.S., also called “trade-dependent maritime realms” by some

academics, have depended on maritime and international trade for economic

survival. If the Eurasians were to exclude the U.S. and Britain from the trade

and economic system of the Eurasian mainland, there would be grave

economic consequences for these “trade-dependent maritime realms.” This was what

Napoléon Bonaparte was trying to impose through his Continental System in

Europe against Britain and this is also one of the reasons for the survival

of the Iranian economy under American sanctions.

Two blocs

are starting to manifest themselves in similarity to the

geographic boundaries of George Orwell’s novel Nineteen

Eighty-Four and Mackinder’s Islander versus Continental scheme; a

Eurasian-based bloc and a naval-based, oceanic bloc

based on the fringes of Eurasia as well as North America and Australasia. The

latter bloc is NATO and its network of regional military alliances, while the

former is the reactionary counter-alliance formed by the Chinese-Russian- Iranian

coalition as its nucleus.

Mahdi Darius Nazemroaya is an independent

writer based in Ottawa specializing in Middle Eastern affairs. He is a Research

Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization

(CRG).

NOTES

[1] Mahdi Darius Nazemroaya, The Sino-Russian Coalition: Challenging

America’s Ambitions in Eurasia, Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG),

August 26, 2007.

[2] Iran, Oman to develop joint oilfields,

Press TV (Iran), August 25,

2007.

[3] Iran to lay Caspian-Oman seas oil pipelines, Mehr News

Agency (MNA), August 27,

2007.

[4] Azerbaijan

interested in ties with SCO - official, Interfax, August 25,

2007.

[5] Leila Saralayeva, Russia, China, Iran Warn U.S. at

Summit, Associated Press, August 16, 2007.

[6] Putin heads

for Austria, energy high on agenda, Reuters, May 21, 2007.

[7]

Russia, Austria to open gas storage facility - Putin, Russian News

and Information Agency (RIA Novosti), May 23, 2007.

[8] Outrage

at ‘old Europe’ remarks, British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC),

January 23, 2003.

[9] Zbigniew Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy

and Its Geostrategic Imperatives (NYC, New York: HarperCollins

Publishers, 1997), p.204.

[10] Roman Kupchinsky, Turkey: Ankara Seeks Role As East-West

‘Energy Bridge,’ Radio Free Europe (RFE), August 27, 2007.

[11] These figures are

based on calculations that are built on mid-2006 statistical figures from British Petroleum (BP). They are based on imports and exclude each E.U.

member state’s domestic or indigenous production.

British Petroleum (BP), Quantifying Energy: BP Statistical Review of World Energy June 2006 (London, U.K.: Beacon Press, June 2006), p.22.

bcm = billion cubic metres

1 bcm = 263.96 billion gallons

Total amount of natural gas imports projected for European energy markets: 139, 960 bcm.

139, 960 bcm = 100% of natural gas imports

Total amount of natural gas imports projected from Algeria: 4, 580 bcm.

4, 580 bcm/ 139, 960 bcm ≈ 0.037 bcm

0.037 bcm X 100 = 3.27% ≈ 3.3%

Therefore: 4, 580 bcm ≈ 3.3% of natural gas imports

Total amount projected from the Middle East, Caspian Sea, and Central Asia sources: 83, 140 bcm.

83, 140 bcm/ 139, 960 bcm ≈ 0.594 bcm

0.594 bcm X 100 ≈ 59.4%

Therefore: 83, 140 bcm ≈ 59.4% of natural gas imports

* Calculations include Egyptian natural gas reserves.

Total amount projected from Russia, Caspian Sea, and Central Asian sources: 47, 820 bcm.

47, 820 bcm/ 139, 960 bcm ≈ 0.3416 bcm

0.3416 bcm X 100 = 34.16% ≈ 34.2%

Therefore: 4, 580 bcm ≈ 34.2% of natural gas imports

[12] Mahdi Darius Nazemroaya, The Globalization of Military

Power: NATO Expansion, Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG),

May 17, 2007.

The Security and Prosperity Partnership (SPP) in

North America between Canada, the United States, and Mexico is also related to

this parallel drive in Eurasia and the Mediterranean littoral to ensure access

to energy resources. Under the framework of the SPP both Mexico and

Canada are obligated, without choice, to supply the United States with its

energy needs, even at the expense of Mexican and Canadian national, economic,

demographic, and environmental interests. The matter of energy supplies has been

transformed into a security issue. There is a strong link between NATO, E.U.,

and North American energy initiatives in this regard.

[13] Halford John Mackinder, Chap. 3 (The Seaman’s

Point of View), in Democratic Ideals and Reality (London, U.K.:

Constables and Company Ltd., 1919), pp.38-92.

[14]

Ibid., p.88.

“The Heartland, for the purposes of strategical

thinking, includes the Baltic Sea, the navigable Middle and Lower Danube, the

Black Sea, Asia Minor, Armenia, Persia [Iran], Tibet, and Mongolia. Within

it, therefore, were Brandenburg- Prussia and Austria-Hungary, as well as

Russia — a vast triple base of man-power, which was lacking to the

horse-riders of history [a reference to the people’s of the Eurasian steppes

that invaded Europe and the Middle East, such as the Iranic Scythians, the

Magyars, and various Turkic tribes]. The Heartland is the region to which, under

modern conditions, sea-power can be refused access, though the western part of

it lies without the region of the Arctic and Continental [Eurasian]

drainage. There is one striking physcial circumstance which knits it graphically

together; the whole of it [the Heartland], even to the brink of the Persian

Mountains [the older English name for the Zagros Mountains] overlooking torrid

Mesopotamia [Iraq], lies under snow in the winter time (Chap. 4,

p.141).”

[15] Supra. note 12.

“Aside from the global

naval force being created by the U.S. and NATO, a strategy has been devised to

control international trade, international movement, and international waters.

The Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI), under the mask of stopping the

smuggling of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) components or technology and the

systems for their delivery (missile technology or components), sets out to

control the flow of resources and to control international trade. The policy was

drafted by John Bolton, while serving in the U.S. State Department as U.S.

Under-Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security

(Nazemroaya, NATO Expansion).”

Mackinder also argued for a

super-navy under the control of the League of Nations that would control Germany

and Russia: “None the less the League of Nations should have the right under

International Law of sending War fleets into the Black and Baltic Seas (Chap. 6,

p.215).” This is part of Mackinder’s solution to securing the Eurasian Heartland

through what he called an “internationalisatio n” process in

Eastern Europe and the Middle East.

SOURCES FOR

MAPS

[1] Jan Horst Keppler: Institut français des relations internationales (Ifri) Energy Program of the Université Paris Dauphine, France (International Relations and Security of Energy Supply: Risks to Continuity and Geopolitical Risks).

[2] Nabucco Gas Pipeline International GmbH.

[3]

Mahdi Darius Nazemroaya, Centre for Research on Globalization

(CRG).

[4] Der Standard, Austria.

[5] Nabucco Gas Pipeline International

GmbH.

NABUCCO GAS PIPELINE INTERNATIONAL GmbH PROPERTY RIGHTS

NIC has full

and exclusive property rights (e.g., ownership, industrial property rights,

copyrights) regarding the map material provided. The publication of this

material can not be construed as the granting of a license or of any other

right. The material made available are for private use and information only

and must not be commercially reproduced, presented, distributed, or used in any

other form unless prior written consent by NIC has been

obtained.

RELATED

ARTICLES AND REFERENCES

America’s

“Long War:” The Legacy of the Iraq-Iran and Soviet-Afghan

Wars

War and the “New World

Order”

The March to War: Détente in the

Middle East or “Calm before the Storm?”

The Globalization of Military Power:

NATO Expansion

Global Military Alliance: Encircling

Russia and China

Plans for redrawing the Middle East:

The Project for a “New Middle East”

Nabucco Gas Pipeline Project: Gas

Bridge between Caspian Region/ Middle East/ Egypt and

Europe

Global Research Articles by Mahdi Darius Nazemroaya

Please support Global Research

Global Research relies on the financial support of its readers. Your endorsement is greatly appreciated